One reason that activists of different classes tend to do things differently is that they often join groups in different movement traditions.

Each movement tradition has roots in a particular class and racial composition. Each was formed during a particular political/economic moment in US history. Ideas about how to make social change and run organizations have been carried down to influence today’s activism.

For definitions of these class paths, see the Class Paths Quiz and Glossary.

Community Organizing Tradition

Examples: local groups affiliated with the Industrial Areas Foundation or the National Welfare Rights Organization

The Midwest Academy trains community organizers in the methods pioneered by Saul Alinsky and laid out in the much-used manual, Organizing for Social Change (Bobo et al.)

The class composition of community groups can vary, but in the Missing Class study, the majority of members were working-class, lower-middle-class or in long-term poverty.

The most common complaint by members of community groups was the difficulty of recruiting and retaining poor and disempowered working-class people. Many groups relied heavily on the same one leader or small number of leaders for years or decades.

Labor Movement Tradition

Examples: coalitions such as Jobs with Justice, which bring together unions and community groups

Union membership varies by the occupations represented, from working poor service worker to lower-middle-class skilled trades to professional-middle-class teachers. Union leaders are mostly college-educated professionals who may or may not have come up through the ranks.

Coalitions run by unions often have class diversity, with many straddlers (first-generation college graduates), many professional-middle-class union staff and allies, and a few working-class rank-and-file members.

Unions are different than voluntary groups, and tend to have a top-down hierarchy rarely seen in non-labor activist groups. But they also rely on voluntary turn-out to meetings and picket lines. The biggest complaint from members of labor-based groups in the Missing Class study was low turnout.

Professional Antipoverty Advocacy Tradition

Example: Local affiliates of the National Association of Social Workers Advocacy Network

Typically the members of antipoverty advocacy coalitions were volunteers working on the same problem they dealt with in their day job, such as lack of affordable housing, health care access or poor schools. The coalition membership may include clergy, social workers, teachers, lawyers and human services managers as well as concerned members of the public. In the Missing Class study, all these groups were led by professionals of color who saw themselves as giving back to the community.

While most members college-educated professionals, in class background these groups are more diverse. Some straddlers (first-generation college graduates) join advocacy coalitions as a way of staying in touch with their working-class roots and giving back to the community.

The most common complaint by the members of professional antipoverty advocacy coalitions in the Missing Class study was competition among members for funding and positive publicity.

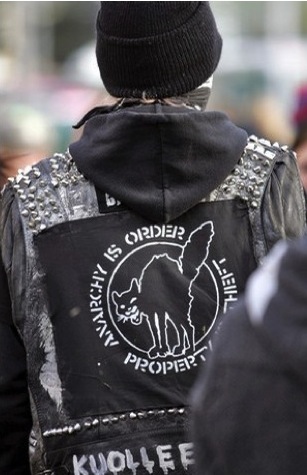

Anarchist Tradition

Example: Food Not Bombs

Anarchist activists sometimes gather in informal groups, sometimes called “black blocs” for street protests, such as in the globalization movement of the ‘90s and anti-Iraq-war movement in the ‘00s. But there are also more permanent anarchist groups, such as the Anarchist Black Cross.

College graduates who are voluntarily downwardly mobile from professional-middle-class backgrounds are most commonly found in the anarchist movement tradition. In the Missing Class study, anarchist groups had the highest average class background of any movement tradition.

Unlike other movement traditions that are more diverse in race, age, and political views, the anarchist groups in the Missing Class study were mostly white and young and united by shared ideology.

The most common complaints by members of anarchist groups were mistrust between members and disagreements over group process.

Progressive protest and nonprofit tradition

Examples: 350.org and other climate change direct action; affiliates of United for Peace and Justice during the Iraq war

College-educated professionals, disproportionately white, made up the bulk of members in these all-volunteer groups who planned protests and public education on global and local causes. Their most common catchphrase for their political values was “progressive.”

Progressive protest groups are more likely to work closely with funded, staffed nonprofit organizations than are protest groups in the anarchist and militant anti-imperialist traditions. Some are incorporated as nonprofits themselves.

The most common complaints by members of the progressive protest groups in the Missing Class study was too little racial diversity and disagreements over group process. This was the movement tradition with the most focus on the internal workings of the group.

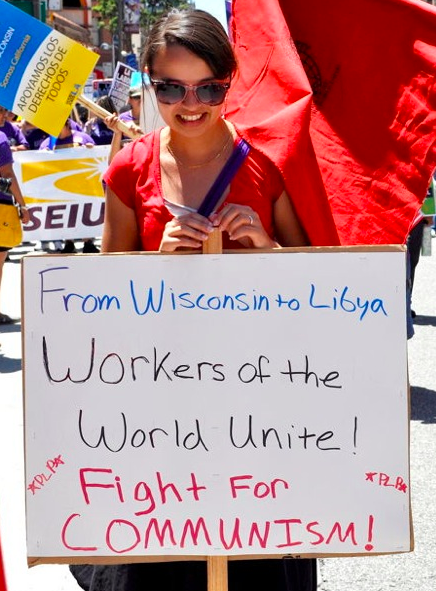

Militant anti-imperialist tradition

Example: Act Now to Stop War and Racism (ANSWER) Coalition, founded by the Workers World Party

In group composition, this movement tradition matches the progressive protest tradition: disproportionately white, and heavily college-educated professional in background and/or current class. The difference between these traditions, which often clash in coalitions over nonviolence codes and tactics, is political ideologies.

The biggest complaints by members of a militant anti-imperialist group in the Missing Class study were rancorous conflicts within and between groups and low turn-out.

For more information on the class cultures of each movement tradition, see Chapter 4 of Missing Class.